This is a short story I wrote last year for an internal work publication, as an imagination exercise: how would the world look like in 20 years? I’m republishing it here, adapted slightly to remove the more obvious name-dropping. If you’re looking for bloody conflict, giant robots / probing aliens or other such bleak dystopian tales of woe, I’ll have to disappoint; as I hope to still be around by the time this takes place, I’d rather live here than in a post-nuclear holocaust desolation. Enjoy!

* * *

The gradual light of dawn and a soft chime of wooden pipes woke her gently from her slumber. Eyes closed, body unmoving, respiration carefully measured, she feigned sleep. It was her little morning game, testing his powers of observation.

The gradual light of dawn and a soft chime of wooden pipes woke her gently from her slumber. Eyes closed, body unmoving, respiration carefully measured, she feigned sleep. It was her little morning game, testing his powers of observation.

“Good morning, Dara.”

She almost always lost though. He seemed to know exactly when she was awake. Which, she strongly suspected, made the handful of times when she won rather suspicious. “Good morning, Stephen.”

“Slept well?” “Can’t complain,” she said with a smile and jumped for the shower. “Are the kids awake already?” “Not yet. What would you like for breakfast?” “Just coffee, thank you, Stephen. And don’t patronize me!”

He had a tendency to oversell the importance of the first meal of the day. Just as well that he didn’t try it today. Her heart just wasn’t in it.

The water was just cold enough to chase away the last cobwebs of sleep from her eyes. “Stephen, agenda for today?”

The glass door of the shower suddenly lit up with her calendar items: blue glowing neon for work items, bright green for personal, orange for shared / FYI and a red cancellation. The lunch meeting, it seems, was not to be. But she wouldn’t look this particular gift horse in the mouth.

“Stephen!” “Yes, Dara?” “I’m having lunch with the kids today. Could you please schedule us an hour? Indian fusion, if you can find a good one in Cairo. They should be getting more in touch with their cultural heritage, I should think.”

“Of course.” Stephen’s educated, British-accented voice was somewhat muffled by the shower stall, but nevertheless she allowed herself a moment to luxuriate in the sound. It was modelled after a famous 20th century comedian and activist by the name of Stephen Fry. One of her father’s favourites, that one. She liked the name, too; it made him sound like an invisible Victorian butler.

“I’ve also arranged for transportation, ma’am.” She smiled a little. It seemed her assistant could still surprise her. “A Qi will pick you up at 11:45 in Saqqarah.”

* * *

She grabbed her steaming coffee from the counter. Majid and Alia looked up from their cereal bowls. She kissed them lightly on the top of their heads, then made for the door. “Mama’s got to run. No sharing today; Stephen ordered a car for you. But I’ll see you at lunch, ok? Have fun in school!” “Bye, mom!” “And Majid, listen to your big sister, ok?” she threw over the shoulder, already halfway through the entrance. A grudging 10 year old acknowledgement chased her out of the building.

Her Qi was waiting outside. She sighed, sipped at her coffee and got in. The fleet of driverless electrical cars, with their polarized glass canopy and specialized AI drivers hooked into a regional planning centre would have been unthinkable 20 years ago for Egypt. Luckily, things changed. She tapped her watch, which caused the windshield immediately in front of her to turn black and accept visual and tactile commands. She pulled the plans for the aqueduct and the desalinization plant with subvocalizations and gestures long turned into routine and started examining the B12 sector. Then made up her mind and called Siew Lee.

“Morning, Dara. En route already, I see.” “Morning, Lee. Afraid not. I looked it over one more time, and I think you’re ready to take care of this on your own. Besides, I have a meeting with TNG Solar about that molten salt reactor they’ve been shopping around. I think they should be the one to build it for us.”

He smiled, taken by surprise. “Are you sure? I mean…” “Course I’m sure. ” A well-practiced flick of her fingers pulled up a list of repair audits; she quickly located one and forwarded the relevant order history. “I’ve just sent you the bill of materials from last month’s issue on the Delta 2 pump. The cases look quite similar, so go ahead and order it. I can double-check your repair schedule before lunch, if you want, but I have complete confidence in you.” “Thanks, Dara. I won’t let you down!” She smiled. “Good luck. Bye, Lee!” Another flick and she cut the connection.

In a few minutes, automated factories in Germany, Ireland and Iran would receive their respective orders. Past experience showed that the order would be there in about a week. In fact, given the nature of the aqueduct malfunction (which was public information after all) and the past ordering pattern from her desert-forming company, chances were that the forecasting algorithms already predicted the order and the production was already set up, just waiting for the final “go”. And Lee was more than capable of dealing with the outcome. Besides, the temporary rerouting held through the night, and the main project was still on schedule.

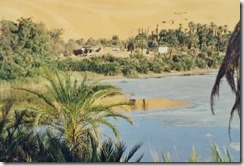

It was one of the most ambitious projects of her generation. Reclaiming the desert had been a dream ever since Egypt, once the breadbasket of the Roman empire, had fell under the rule of the sand dunes . Desalination plants processed sea water via reverse osmosis and pushed it via reinforced glass aqueducts (sand had its uses) to the enrichment stations, where it would be mixed with nutrients – mainly from algae farmed off-shore – and onwards to the irrigated argan tree and oil palm forests that slowly turned the yellow desert glare into a sea of green. The goal was self-sustainability; the massive initial investment from World Global Climate Control Centre having been matched year after year by private investments playing the long game.

TerraForma, the consortium that took on this challenge, was unique in that it gathered the best and brightest from various companies around the globe, lending their expertise in their respective areas. Dutch planning and German engineering met Chinese solar tech and Japanese miniaturization – to name but a few of the nations that were represented in the project. And now Dara Stephens, née Banerjee, project manager and Harvard graduate cum laudae, daughter of a Mumbai rickshaw driver who turned his humble business into a logistics empire, got to fight for the rights to deploy the latest Australian molten salt solar reactor design into the heart of the soon-to-be-extinct Sahara.

* * *

The meeting was shorter than expected. Her initial plans for 10 reactor deployments was met with enthusiasm from the stocky, jovial Melbourne native representing TNG Solar, who seemed to regard this engagement as a proof-of-concept for an ambitious deployment in the Northern Territories. “And who knows, when you guys are done here, maybe you’ll visit us Down Under. We’ve got some deserts of our own to take care of.”

She smiled at the memory, already on the way to a well-deserved lunch, when her watch chimed. A touch and a well-known voice sprang from her left earring. “Ma’am, I just received confirmation on your order. The drone will be en-route in 15 minutes.” She drummed her fingers on the pseudo-leather of the seat. “Could you reroute it to the restaurant, please? It’s Alia’s present after all.” “Of course.” “Thank you, Stephen.”

She checked her schedule for the afternoon. Two more meetings, but none with face-time required, as the office lingo went, so she could work from home after lunch. Checking into the Virtual Office, the car canopy obliging her once more with the familiar black, she saw that the order placed by Lee already had solid confirmations and delivery estimations 5 days from now. That should keep him happy for at least a week, she thought, right until he’ll run into the subcontractors “midday-sun” fees. With a guilty smile, she admitted to herself that she looked forward to seeing him haggle his way out of that one. The Egyptian construction company they hired was nice enough, but enthusiastic negotiations were so ingrained in the local psyche that few visitors were ever able to get the better of a deal. She was an exception; but she learned from the best. Her father could out-haggle a Nairobi fisherman – and that was no faint praise.

* * *

As presents went, Alia’s wasn’t spectacular: a vintage iPhone with the WiFi module replaced to be able to connect into the modern CommNet. But Dara knew her daughter well, and a squeal of delight confirmed it, much to her satisfaction. Her interest in retro-hacking was recent, but enthusiastic. Fifteen minutes into the meal she was still playing with the thing, trying to get it to talk to a so-called retro appstore maintained by like-minded nerds somewhere in Pakistan.

“They were pretty dumb. I mean, you had to touch them all the time, and they didn’t even have voice commands.” It seemed the 10 year old’s enthusiasm did not extend to his big sister’s toys.

“Yes it did! Look!” A few minutes and turned heads later Dara began to question the wisdom of her decision to have this particular present delivered to the restaurant. Fortunately, a stern motherly look still had the desired effect (not for long, Dara sighed, the teenage years are fast approaching) and the rest of the meal went by in a much more companionable fashion.

“It’s still dumb,” Majid commented as they finished their deserts. Alia deigned to ignore both the comment and its author, with an exasperated sideways look that Dara recognized too well. As their father always liked to say, they learn it all, whether you want to teach it or not.

* * *

“… and then she played with that annoying pseudo-AI voice interface until I thought Stephen was going to take offence and shut me out,” she laughed, remembering. Daniel’s laugh came 3 seconds later, as the signal bounced through the network of comm satellites and reached him on-board the ISS Ophelia, the high-orbit biotech lab working on some I’d-tell-you-but-it’s-complicated 0grav project that was stealing her husband from them for 6 months at a time. She got used to the delay, and the absence; you got used to a lot of things in time, it seems. Humans are such amazingly adaptable creatures, she thought to herself.

“Speaking of Stephen; I hope you’re not replacing me with an AI, priya.” The warmth of his smile melted the distance between them.

“Not a chance. Be safe, jaanu.” She ended the call with what has become her mantra for all those times he was a way . Two more weeks , she thought, two more weeks and then he’s back with me. And this time it’s New Zealand, and we leave all the communicators at home. He promised.

“Stephen!” “Yes, Dara?” “Please schedule a meeting as soon as you can with R&D. I’d like to talk to them about Jasper’s fluid models; they were achieving an efficiency increase of 16%. And book us a flight home for the weekend. Don’t tell my dad; it’s a surprise.” “Of course, ma’am.” She dismissed the last of the mails and closed her eyes. “Good night, Stephen.” “Good night.”

The lights, already dimmed and red- shifted to stimulate her circadian rhythm, slid down towards oblivion. Outside, a prickle of stars shone above the night desert.

In her dreams, the desert was green.